The world’s aging population may not be a risk to the global economy after all

The global population is aging as life expectancies rise and fertility rates decline — a situation that is often described as a “demographic time bomb,” in which the economic support for a growing number of older people depends on a shrinking working-age population. But increasing longevity and a healthier aging population suggest a much more positive economic outcome, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

On their face, some demographic statistics appear worrisome: Median life expectancy in developed economies has risen by 5% since 2000, from 78 to 82 years, and the portion of the population that is of working age (15-64 years) has been falling, according to a team led by Kevin Daly, co-head of Central & Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa economics at Goldman Sachs Research.

Given such trends, one might expect the labor force as a share of the total population to have fallen during the same period. But in fact, the share of the total population that is employed has actually increased. Since 2000, the effective working life in developed economies has increased significantly, the research finds. In richer countries, the dependency ratio (the population of dependents relative to workers) has actually fallen despite the decline in birth rates.

This trend towards extending working lives shows little sign of abating and is taking place in countries with minimal changes to pension laws, suggesting an adaptive response to increased longevity, Daly writes. “Increasing life expectancy is fundamentally a good thing,” he says. “Population aging is one less thing to worry about.”

How long are people expected to live now?

Human lifespans are getting longer just about everywhere in the world, and older people are healthier than their ancestors. The average global life expectancy has risen from 62 to 75 years over the past half century. In developed economies, life expectancy has risen from 72 to 82 years, and gains are coming faster in emerging economies, where life expectancy has increased from 58 to 73 years. US life expectancy has declined slightly in the past decade, but this is an exception to a consistent and global trend. Extrapolating the trends of the past 150 years, the average person born today might live to 110.

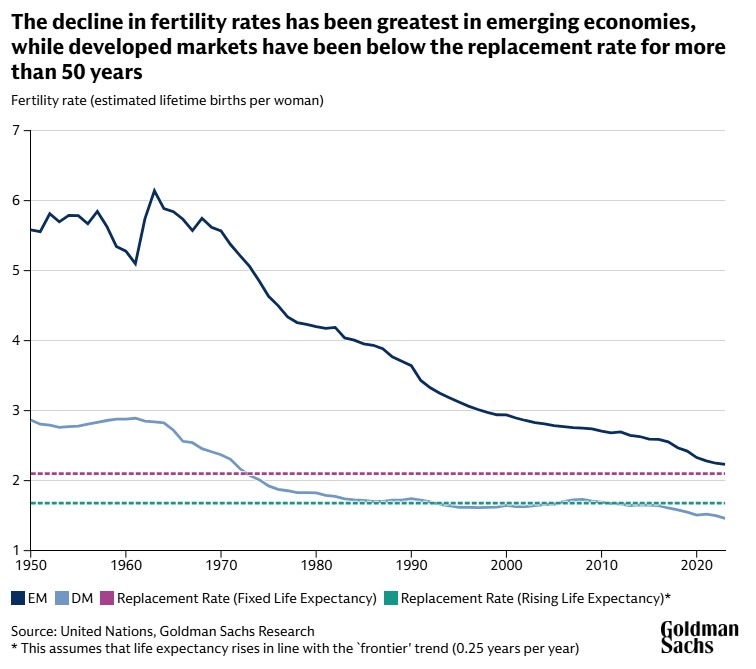

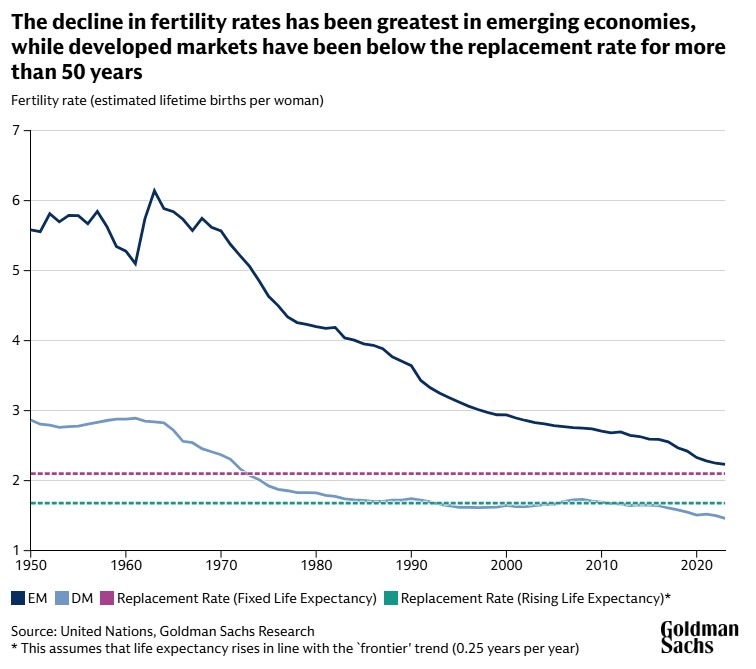

Along with longer lifespans, declining fertility is the other demographic trend contributing to an aging global population. The global fertility rate — the estimated number of births a woman will have in her lifetime, based on current birth rates — peaked at 5.4 in 1963, dropped to 4.1 in 1975, and continued falling in subsequent decades to reach a global fertility rate of 2.1 today.

People are becoming healthier around the world

People today are healthier as they age, unlike their ancestors, Daly writes. A 70-year-old in 2022 had the same cognitive ability as a 53-year-old in 2000, according to a recent International Monetary Fund study of a large sample of individuals from both developed and emerging economies. The physical robustness of that 70-year-old corresponded to someone who was 56 in 2000.

“The fact that we are not only living longer but also slowing the process of aging throughout our lives raises an important economic point,” Daly writes. If increases in life expectancy extend the amount of time spent in the traditional idea of frail “old age,” more goods and services tailored for seniors will be needed. But if a more accurate picture is that the onset of “old age” happens later and later in life, an increased demand for products and services catering to an older population is less certain.

“In a very tangible sense, 70 is the new 53,” he adds.

How does an aging population affect the economy?

A primary concern with an aging population is how it affects the so-called working-age ratio, the portion of the population in the 15-to-64 age range. This declines as more people reach retirement age, raising the fear that GDP per person will dwindle. In developed economies, the working-age ratio reached a plateau of around 67% from 1985 to the early 2000s but has since dropped to 63% and is projected to fall to 57% by 2075.

The key question, though, is whether employment falls on a one-for-one basis with changes in the working-age ratio, Daly says. Assuming this to be true “appears unduly pessimistic,” he writes. Age-specific employment rates are constantly changing and merely looking at the portion of the population in that 15-to-64 age range doesn’t tell the whole story.

How much longer do people need to work to offset the effects of population aging? For developed economies, offsetting the peak-to-trough decline in the working-age ratio would require a 15% increase in the average effective working life between 2000 and 2075.

The good news is that this transition is already well underway. The researchers find that since 2000, average working lives have already increased by 12% (from 34 to 38 years). The result is that, despite longer life expectancy and declining working-age ratios, the average share of life spent actively participating in the labor market has actually risen, from 44% to 47%.

Several factors have contributed to this increase, including a shift away from manual jobs — where early retirement is more common — and rising female participation in the workforce after childbirth.

“While raising official retirement ages can help address the fiscal challenges of government pensions in an era of growing life expectancy, it doesn’t seem to be an essential requirement for people to extend their working lives,” Daly adds.

This article is being provided for educational purposes only. The information contained in this article does not constitute a recommendation from any Goldman Sachs entity to the recipient, and Goldman Sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, investment, accounting, or tax advice through this article or to its recipient. Neither Goldman Sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this article and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed.

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newletter via email.